SERMON 138A: On Dissimulation

An Introductory Comment

In retrospect, John Whitehead could conclude that John Wesley had been, if anything, candid past the point of prudence.1 Here, in this early sermon and two fragments on the same theme, we have an interesting testimony to his lifelong hatred of cunning, deceit, and lying in all its forms.

There had been, of course, an abundant controversy on the question of 'dissimulation', what with the violence of seventeenth-century English life and the tenuous fortunes of public life in the eighteenth century. Both Gilbert Burnet and Jonathan Swift had seen dissimulation as a prevalent way of life.2 Dissembling had been defended as a necessary evil in politics and society by Lords Bacon and Bolingbroke.3 Sir John Suckling had praised it in verse,4 and Bernard Mandeville had celebrated it in his cynical Fable of the Bees (1714; 2nd edn., 1724). Wesley may not have read Mandeville in 1728, but he knew the world that Mandeville was pillorying, and he must also have been aware of the torrent of denunciation that the Fable had drawn down upon itself from men as diverse as Richard Fiddes, John Dennis, and Archibald Campbell. Later, he would himself denounce Mandeville as worse than Machiavelli, since, as he put it, 'the Englishman [sic] loves and recommends vice of every kind . . . as absolutely necessary at all times for all communities.'5

But Wesley stood unmoved in a contrary tradition, that cherished sincerity and repudiated all its opposites as hypocrisy. He had the backing of Robert South, who blasted away at dissimulation in sermon after sermon.6 Earlier, Henry Smith had denied that it was any necessary part of 'public policy'.7 Moreover, there was William Sheppard's Sincerity or Hypocrisy; Or, the Sincere Christian and Hypocrite in their Lively Colours, Standing One by the Other (1658). Most decisively, though, he had the examples of his parents before him, and their lifelong habits of forthrightness and plain dealing. Hence, on the very threshold of his ministry, he was moved to stern denial that dissimulation is a sincere Christian's option under any circumstance.

The following sermon and its two related fragments express the young Wesley's views. Later, he will repeat them and his condemnations of lying, even with an alleged good intention, in Nos. 24, 'Sermon on the Mount, IV', IV.3; 52, The Reformation of Manners, IV.4-5; and 90, 'An Israelite Indeed', a second sermon on John 1:47.

The holograph of the full sermon here survives in the Morley Collection in Wesley College, Bristol. It is on thirteen numbered pages in the abbreviated longhand already mentioned. The paper cover has the number '17' inscribed on it in Wesley's hand (indicating its place in the early sermons). Beneath this is a note, in Adam Clarke's hand: 'Mr. J. Wesley's Sermon on John 1:47, Behold an Israelite Indeed, etc. Jan. 17, 1728.' Near the foot of p. 13 is a further note in Wesley's hand: 'Jan. 17, 1728, tr[anscribed], 22 m[inutes]' and '2 1/2 aftern[oon]' (i.e., 2:30 p.m., the time he had finished transcribing his fair copy). On the back cover there is a final notation of Wesley's, 'At Epworth'.

The first fragment on Rom. 12:9 would appear to have been a first draft of the proem of still another sermon 'against dissimulation', with no indication of date or provenance, but probably from the same general period. It may be seen, as a single page, in the Elmer T. Clark Collection of Wesleyana in Lake Junaluska, North Carolina.

The second fragment looks more like the remains of an uncompleted draft of what had been designed as a whole sermon. It has survived as part of the Colman Miscellany in the Methodist Archives in Manchester, in a form that poses many puzzles. There are twelve pages; the first two are blank, the third is numbered '3', the fourth has revisions for insertion on the facing (fifth) page, the sixth with revisions of the text on its facing page (numbered '4'). The eighth page is blank, the ninth has some text but is unnumbered, the tenth is blank, the eleventh is numbered '5' and contains only two lines of text, ending with an unfinished sentence, the twelfth page is blank. There are numerous erasures, revisions, and additions. Its text, as presented here, is an attempted reconstruction of what may have been Wesley's intentions as they can be gathered from the document as it stands.

The connection between the two fragments is obscure. What is clear is that,

whether we are dealing with two sermons (the first one on John 1:47, the

other on Rom. 12:9) or with three, the arguments in all of them are commonplace

enough to see in all of this material an expression of a single idea with

different facets: that dissimulation has no successful defenders―only practitioners―that

it is actually a form of folly (as well as a vice) because it is finally

self-defeating; dissemblers are often hard-pressed to maintain their disguises.

The conclusion is also a Christian commonplace, viz., that, therefore,

honesty is not only the best policy but also the easier one in the long

run. Nothing here, either in the sermon or the two fragments, goes beyond

Sheppard or South or Tillotson. Thus, whatever the complications of these

texts, the resulting impression is plain enough: here is the gospel of

moral rectitude as understood by a young Anglican who was both a fledgling

don and, at the time, an apprentice country cleric.

On Dissimulation

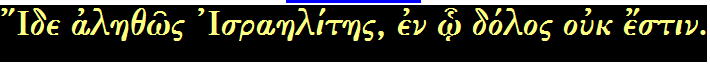

John 1:47

Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!

[1.] 'Tis too common an artifice with our enemy to persuade us into one sin to hide another. And an artifice it is, too commonly successful. When he has once led men into that strong delusion1 that their temporal is their supreme interest, they are easily induced to sacrifice everything to it, and stick at nothing that may promote it. The more anything tends to advance this, the more carefully they embrace and preserve it. And finding reputation to do so in an eminent degree, to be of great use in their temporal affairs, they had rather sin twice against their conscience than once against their character.2

[2.] Particular sins on particular occasions he recommends to them for

this purpose. But a general one there is that answers all, a habit [of]

dissimulation, the practice directly opposite to that which God recommends

to Christians. This his favourites are seldom without, and they find it

indeed of eminent service. A man may cover some vices by other methods,

but this is equally a cover for all. The whole person, unless when he has

a mind to appear, is by this made quite invisible; and when he has a mind

to appear, 'tis usually in a shape quite different from his own.

[3.] G.D.3 To preserve them who have not this reason for dissembling from

deceiving both themselves and others, having already given you a view of

the beauty, honourableness, and wisdom of that godlike virtue, sincerity,4

my design is now to paint in opposite colours the opposite vice, insincerity:

to show the baseness, deformity, and folly of it―how mean, odious, and

imprudent it is to dissemble.

I.[1.] If an estimate can be made of the baseness of any practice from

the baseness of its original, where is it possible to find one that had

a meaner than artifice and dissembling? It sprung first from the basest

being in nature: the devil was the father both of this and [of] lies.5

The devil was the first that had occasion for either, for he was the first

that wrought wickedness. And this immediately laid him under a necessity

of dissembling, to hide it: wholly, if he could, from such as dissented

from it, and in part from his companions. These he deceived by seeming

better than he was, from the beginning of his apostasy; and had he not

done so, had his whole pride, malice, and envy appeared in the infancy

of his rebellion, 'tis highly probable a third part of the host of heaven

would never have listed under his banner.

Such Satan was before the world began, and such has he been ever since.

His fellows indeed he can deceive no more, so that he has been forced to

employ his skill on new objects; and what objects could he find so proper

for his purpose, after his fellows, as the children of men? They had neither

too much understanding, nor too little: not so much as to put him out of

hopes of success, without which he would not have dared to attempt them;

nor so little as to prevent their being accountable for his success, without

which it would not have gratified his malice, and so he would not have

cared for it. On these he has practised ever since; and practised so long

till he has taught them his art; till he has taught them, with other of

his dispositions, this disposition to deceive so perfectly that perhaps

'tis only the want of equal natural powers that hinders some of them from

equalling their master.

2. Little more honour, we may suppose, can dissembling gain from these

its practisers than from its author. If he who gave them their parts, the

master of the house, be Beelzebub,6 what can we say in praise of his household?

We can say that they resemble him in several respects: they were both created

upright; both had it [in] their power to continue so; but both wilfully

declined it. The same course both took when sensible of their fault―not

to amend, but only to cover it, to sew figleaves together to hide their

shame,7 without one thought of removing the cause of it. By this means

is one become the most contemptible of men, as the other is the meanest

of angels.

3. By this means his work multiplies on his hands: he must lay veil upon

veil, must take as much care to cover his dissimulation as he did by that

dissimulation to cover anything else. For so very despicable is a known

dissembler in the eyes of all men that scarce any man thinks it worth while

to dissemble the low opinion he entertains of him. So very generally is

dissimulation despised that it never yet has found a defender.8 Almost

all other vices in their turns have found some son of Belial to plead their

cause: but this is of so evidently contemptible a nature, so perfectly

base and dishonourable, that never of all its practisers hath one appeared

who durst openly engage in its defence. Its best friends, as well as its

enemies, give it up in everything but their practice, both reason and the

general sense of the world making it utterly indefensible.

II. Yet well it were for the crafty, if this were [all]; if they were only despised by those that knew them. But 'tis seldom so well with them. Few men stop here; 'tis an easy step from contempt to hatred. An open, generous enemy we make allowances to, and often wish to make a friend of. But one that smiles in our face while he prepares to wound us is as odious as dishonourable.9 And there is little to choose whether he thus conceals real enmity under the appearance of indifference, or whether he conceals real indifference under the appearance of love. 'Tis hard, even for a Christian, so perfectly to get the mastery over his temper as not to conceive some aversion to one that has a habit of doing either. He who was not withheld by Christianity would make no scruple of giving a loose10 to his resentment; would almost think it meritorious to hate such wretches more sincerely than they love anything but their [own] interest.

Where indeed could sincerity of hatred be better placed, were we not restrained

by our religion? As the more benevolent any being is the more it deserves

the love of others, so the less benevolent, the more malicious and revengeful

a being is, the properer object it is of hate. But 'tis a question whether

they be capable of love, who are given over to dissembling―that they are

fully capable of hatred, malice, and revenge, we have frequent and melancholy

proofs. The nature of love is sincere, plain, and open; and so is the nature

of discretion. This therefore is well consistent with it―whether cunning

be may be doubted. For where one [is], there is no need of the other. Why

should a man dissemble when he loves? If his goodwill appeared, would he

be ever the worse? Is it not rather likely to procure him a return of goodwill?

And that no one, surely, will be afraid of! No, it is not love, but hate,

that men use to dissemble. He therefore that dissembles with all men gives

a strong presumption that he loves none; none, at least, so well as his

[own] interest.

And how detestable a character is this! How nearly resembling that of the

devil, his teacher!11 If he loves nobody, is it at all worse than he deserves

if nobody loves him? And so it fares with the other, the great deceiver

and enemy of mankind―the only creature we know of in the creation that

is entirely unloving and unbeloved.

III. The folly of this base, hateful practice, comes in the third place to be considered. And this we may easily do by observing, first, the ends the dissembler aims at, ends unsatisfactory while they last, and yet incapable of lasting long; and then the means he uses to attain them, which, to say no more of their odiousness and baseness, are difficult, dangerous, and sinful.

1. First, the end the dissembler proposes to himself must be some temporal

advantage. They whose chief end in acting is eternal happiness neither

need nor dare conceal it. But this [temporal] end, whether wealth, honour,

power, or sensual pleasure, if ever he should attain it, when attained,

will not satisfy his desires, will not make him happy, even while it lasts.

All things under the sun―believe him who tried them12―however fair they

may appear at a distance, when we come near them are no better than vanity,

and give more vexation than real delight. The best of them can only please

the sense; but that is not enough to make us happy. The soul, too, before

that can be brought to pass, must have its pleasures, as well as the body.

But where are those to be found? Not in perishable things, but in objects

suitable to its immortal nature.

2. That what he seeks is perishable, as well as unsatisfactory, is another proof of the folly of a dissembler. Though the objects he pursues are but empty and trifling, yet would their value be greater than it is if they would continue with him that acquired them. But he has not only chosen the worse part, but that which soon will be taken away. When he hath spent his life, and consumed his strength in the acquirement, 'what hath he of all his labour, and of the vexation of his heart, wherewith he hath laboured under the sun?'a 'To a man that hath not laboured therein shall he leave all he gained for his portion';13 'for there is neither riches, nor power, nor honour, nor sensual pleasure in the grave whither he goeth'!14

3. Let us, secondly, consider the means the crafty make use of in pursuit

of their wretched purpose. How difficult they are is easy to conceive:

the dissembler has so many parts to play that without the utmost pains

and vigilance he can scarce avoid being out in some. He must seem of all

parties, opinions, and tempers, as those vary with whom he converses. But

how hard is it to shift the scene so often and never be suspected of shifting

it at all! The very number of his parts carries difficulty with it, were

each of them ever so easy. But each of them singly is less easy than the

part of an honest man; he follows nature, whom the other directly opposes,

and may therefore depend on her assistance. And wh[ere] nature fails, grace

supplies h[is] want―with which the dissembler can have little acquaintance.

4. This makes his [the honest man's] business as safe as 'tis easy: whereas the dissembler, by the nature of his employ, is exposed to continual danger. He has undertaken to defend so numerous posts that 'tis great odds if [he] can always defend them, if he is not, in spite of all his care, surprised sometime at one or other. Besides, many of them are scarcely tenable long against a prudent, observing man. The least oversight gives the one so irrecoverable an advantage, that all the shifts of the other will not be enough to secure him from the misfortune he dreads above all things: the being divested of his borrowed plumes and shown to the world in his native colours. Nor does he dread it without cause; for whenever this happens all his measures are disconcerted, all his schemes are destroyed; and if he prosecute them still he has farther to go than when he first set out.

5. The sinfulness of this difficult, dangerous practice is the last and greatest instance of its folly. And this no one can long doubt of: for if sincerity be a virtue, then dissembling must be a vice, they being opposite habits; wherefore15 the one, wherever it obtains, must exclude the other. And God tells us himself in express words how he does, and by consequence how we should esteem it: 'The Lord shall abhor,' saith the inspired Psalmist, 'both the bloodthirsty and deceitful man.'16 From which words we not only learn in general that God detests the habitual dissembler, but the degree, too, in which he detests them; as they are ranked with the bloodthirsty in his displeasure, whom we know he is not a little displeased with. And in fact these as well as the other offend, not against his truth only, but his mercy. Few there are that deceive but in order to hurt; though it may be done with all the seeming tenderness imaginable. But that is no proof of their good intention: 'The words of their mouth may be smoother than butter, when war is in their hearts. But those selfsame words, though softer than oil, yet are they drawn swords.'b

'Deliver me, O Lord,' said David, who knew them, 'from lying lips, and from a deceitful tongue.'17 And well might he say so; for experience had taught him that the fruits of them 'were more bitter than death'.18 And if it hath indeed appeared that disembling is base and odious, and in fact despised and hated by God and man; that besides this it is foolish on several accounts, as both proposing to it[self] vain, perishable ends, and using difficult, dangerous, sinful means to attain them; let us join in David's prayer, in the largest sense, and beg that we may neither suffer by deceit, nor act it! But more fervently pray we against the latter, as being by far the greater evil. 'Whoso pleaseth God shall escape from both; but the sinner shall be taken by them!'c